WEST LIBERTY–Yik Yak user @sloppertopper posted: “Which one of you mfs hit my blunt and gave me throat cancer.” This garnered 13 upvotes.

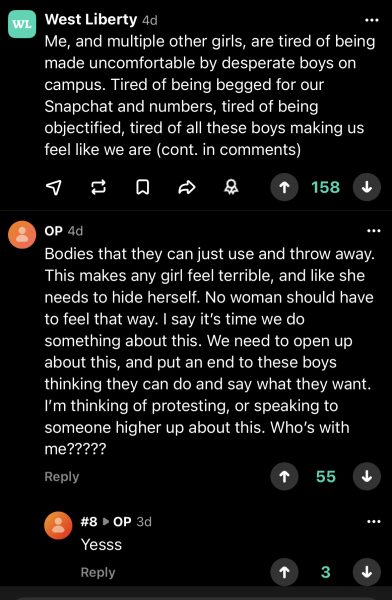

Another post read: “Me, and multiple other girls, are tired of being made uncomfortable by desperate boys on campus. Tired of being begged for our Snapchat and numbers, tired of being objectified, tired of all these boys making us feel like we are (cont. in comments.)” That one racked up 158 upvotes.

Welcome to a normal Tuesday on West Liberty’s Yik Yak.

According to a 2024 EBSCO article, the app was first created in 2013 by Tyler Droll and Brooks Buffington. It was made for college communities confined within a five-mile radius. Anonymous, unfiltered, and unpredictable, Yik Yak quickly became a catalyst for connection.

However, it also became known for its cyberbullying, racism, and harassment, a reason for its shut-down in 2017. Four years later, the app relaunched with a shiny new promise of community regulations. Once again, it’s everywhere on college campuses.

At West Liberty, Yik Yak has worked its way into Bear’s Den booths and party basements. Sometimes it’s helpful, and sometimes it’s brutal. But what do students think when they step away from their feeds?

Rhiannon Christmas doesn’t scroll. As a senior at West Liberty, she’s never downloaded the app.

“I actually don’t have any care into the drama,” she said. “I’d rather keep my peace and not know what people are saying—negatively or positively.”

She admits she sometimes feels left out when people laugh about Yik Yak jokes she hasn’t seen. But she shrugs it off. “If I care enough, I’ll ask people,” she said. “But I’m not desperate to be into it.”

To Christmas, the app feels like a trap for overconsumption. “You get drawn into it, get sucked into the drama, and all of the business you should not be involved in,” she said.

She compared it to other platforms she’s left behind. “I haven’t had Snapchat in five years, and I couldn’t be happier without it. I think that plays a role in how I feel about Yik Yak. If you’re name-dropping an RA or saying a faculty member is awful, those things linger. It can really impact people, so just be careful about that.”

Her final thought: “The people on it are still people.”

Once a Yak is posted, other users can reply to it. A posting can also be upvoted (voted in favor of) or downvoted (voted against) by other users. Furthermore, another user can report a Yak as being offensive. The posting is removed if two or more users report an offensive yak. If a user continually has their postings downvoted or reported as offensive, the user is suspended from

posting.

In addition to its democratic voting system, the app also offers users the chance to earn Yakarma, or reputation points, if they receive enough upvotes.

For a West Liberty junior who asked to stay anonymous, Yik Yak has been the opposite: a daily habit. They’ve collected 16,837 yakarma points, making them the second highest-ranked user on campus.

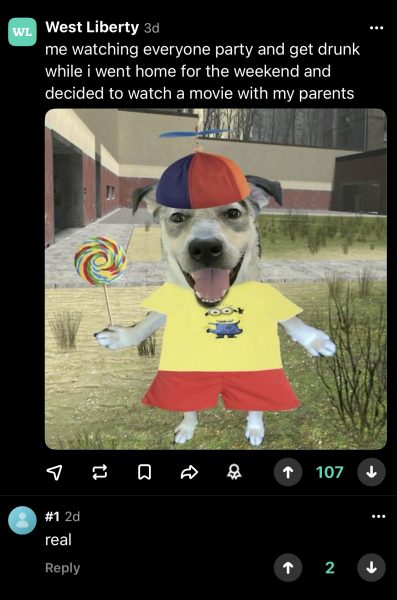

“Now, I’m a fiend for it,” they said playfully. They started using the app freshman year when others wouldn’t stop talking about it. Now, it’s how they connect on campus.

“It’s a good way to know what’s going on—like if the power’s out or there’s a water leak, you’ll see it first on Yik Yak. Oh, the power’s out in this building… there’s a water leak again, get ready for that email,” they said. “Just being able to be connected to people and also not having that judgement of being the person to speak out about something. Not having it attached to me makes me feel more confident to say stuff on there,” they added.

Their posts fall somewhere between funny and practical. “Sometimes I just want to make people laugh. Other times I want to know if people are feeling the same way, like ‘Is anybody else’s hair greasy from this water?’”

Still, they notice a darker side. “People are way meaner on Yik Yak than they are in person. If you just looked at the app, you’d think the school was horribly toxic. But when you walk around campus, everyone’s just doing their own thing, being nice. So, I don’t think it has too much of an effect—except for, like, connecting for parties.”

Their advice to new users: “I only recommend it if your mental health is in a good place.”

Which brings us to the Bungalow, the mythologized baseball house on Yik Yak, where anonymous posts can make or break a Friday night.

It was weird trudging to the house at 10 p.m. on a weeknight. It made my Monday feel like a surreal Friday. The plain beige Bungalow house sat on the street down from the West Liberty police department with LED lights and NCAA signs flooding through the windows.

Do they use Roberts Rule of Order in roommate meetings to plan weekend parties? Do strangers show up on the doorstep just because a Yak says so?

Inside, the roommates gathered: junior Owen Taylor, who goes by OT; sophomore Rocky Serafino; graduate student Ciaran Flanagan; and sophomore Chuck Thomas, who insists on “just Chuck.” Also, if you didn’t know, all of them are also on the university’s baseball team.

However, when it comes to off-campus parties, Yik Yak often tries to decide for them. “We’ll just be hanging out, and then somebody checks Yik Yak, and it says, ‘Bungalow’s throwing at 11,’” OT said. “But none of us ever said that.”

Ciaran shook his head. “The expectation comes with a lot of false information. People will say ‘confirmed’ and we never said that. But then people show up.”

Rocky added, half-joking, half-serious: “What people don’t realize is they think this is just a party house. This is more of a humble abode for us.”

Still, they run it like a democracy. If one roommate sees a post suggesting a party, the group votes. Majority rules. If you’re outnumbered, well, they better get ready for company to come bursting through the earth.

Though, their visibility comes with pressure. “Yeah. Well, I’m like Yik Yak famous,” OT admitted with a half-laugh. “My face is posted like every weekend. Like headshots of my baseball profile. They post just like fabricated stories.”

“Yeah, definitely,” Ciaran said. “It’s just the expectation of like, we’re the only place that will throw a party, and we’ve had multiple discussions. It’s like we might just have to hold out because it’s like we can’t be the only one, the only house people are trashing.”

Rocky agreed. “If we do end up having a party, we’ll let people know. I get a very large amount of texts of Bungalows thrown from Thursday through Saturday every week,” he said. “I mean, I don’t know, it’s just kind of annoying because I’ll just get 15 texts about it every single week and I’m tired of telling people the same exact thing. Like it’s very clear when we’re actually throwing. When we’re not, it’s just spam and junk.”

After a recent party, the annoyance turned into something bigger. Their one-of-a-kind banner and a teammate’s speaker were stolen. “

And we’re like where the hell is the speaker? Looking for it, thinking somebody maybe threw it in like the weeds in the back. Can’t find it. So then I had to reimburse my teammate because it was at my house,” OT said. “So yeah, we were just like all right, I think it’s time to call it quits for parties.”

The missing speaker quickly took on a life of its own. Yik Yak lit up with memes and ransom-style pleas, begging for the burglar to show mercy of their West Liberty weekend outlet.

But the speaker never came back. “I think the anonymous factor on the app just plays a huge part,” OT said. “Anybody can hide

behind a screen and just chat away. So, like, no one’s going to come up and be like, oh, I got your speaker, come get it. But they can do that on the app. And one person can post like a bunch of stuff. It really doesn’t matter.”

Before the night at the Bungalow came to a close, Rocky offered his closing line: “Love is what makes a house a home.” The others laughed. Despite theft and a trashed house after a fun weekend, their relationship remains strong with one another outside of the app.

But not everyone is as resilient as the Bungalow residents.

Lisa Witzberger, Director of Counseling Services, said Yik Yak has even surfaced in student counseling sessions. She reiterates that first-year students and students with mental health challenges are vulnerable to social media and can reinforce feelings of isolation or disengagement.

In a written statement, Witzberger states “I think the app can create a toxic campus environment. One where embarrassing or harassing others may become normalized. However, some studies show that supportive and prosocial messages were more common than bullying ones. These types of messages can foster a sense of community.”

She once again emphasizes the duality of the app. “The anonymity can provide a safe space for students to express concerns without fear of judgment,” she writes. “The anonymous nature often facilitates harmful behavior that can severely impact a student’s mental health.”

So, maybe the truth is exactly what students keep saying: it’s a grey space. The app connects us, but it also divides us. It amplifies humor, but also cruelty. It tells us who’s throwing, even if they’re not.

And maybe that’s the real paradox: for an app built on anonymity, Yik Yak has a way of making its presence felt everywhere, in counseling sessions, classrooms, and even a house full of baseball players who just want a quiet Friday night.

At the end of the day, every post, no matter how grueling, cruel, or funny, still comes from someone who sleeps here, studies here, and tries to carve out a life here, just the same as the rest of us.

West Liberty’s Counseling Services provides a safe, welcoming space for students to talk and find support. Book an appointment through your WINS account, walk into S14 on the Student Union’s second floor, or email [email protected] for more information.