By Daniel Morgan, Advertising Manager

One of the most talked about subjects in higher education, and all education for that matter, is grades. A gradebook is essentially a student’s best friend throughout his or her academic career. However, the availability of grades has been a controversial topic between students, faculty, and administration in recent years at West Liberty University.

An unofficial policy that requires instructors to issue midterm grades to each student, regardless of his or her letter grade, was effective beginning in the fall 2014 semester per the request of the Student Government Association (SGA). Prior to this method, only students who had attained a “D” or “F” standing in a course received those midterm grades.

“We originally pushed for all professors to maintain gradebooks on Sakai,” SGA President Allyson Ashworth said. “But with the amount of grades in classes being different, we think that the new midterm policy works and that it will stay.”

While one would think the recent change is beneficial to students, there are some who surprisingly disapprove of the procedure. Differential views on midterm grades, and grading in general, perfectly illustrate the one phrase that remains true in all aspects of life: you cannot please everyone.

According to a spring 2014 Parent Power Newsletter, “Midterm grades are issued as a cautionary measure to alert students whose course grade is currently a “D” or “F” to take action!” Now, with the new procedure, one can argue that the alertness is gone.

“Sometimes, certain students will see midterm grades that are better than they were expecting, so they can back off on effort a little bit,” Assistant Professor of Journalism Tammie Beagle said. “When this happens, final grades can slip. Sending home Ds and Fs will warn students that they need to step it up, but pleasant surprises can be disastrous.”

While midterm grades do raise a concern for counter-productiveness, as several instructors will note, there is a larger concern for the availability of grades to students.

“SGA promoted the idea because of student frustration in general,” SGA Vice President Megan Bobes said. “With some professors, you never know where you stand.”

According to Ashworth and Bobes, students also inquired about the possible requirement for faculty to keep a gradebook on Sakai. That plan, however, did not pan out, according to WLU’s provost, Dr. Brian Crawford.

“There’s no faculty requirement for Sakai other than to post their course syllabus,” Crawford said. “Some find the gradebook very useful, and others find it useless.”

As for the midterm grades procedure, Crawford understands the faculty concern of instilling a “false sense of security,” but he realizes that students want to know where they stand. “It takes faculty a few extra minutes to report them,” he said, “but they’d still have to calculate the grades anyway.”

WLU President, Dr. Stephen Greiner, was unaware of the midterm grades procedure, but he is ultimately in favor of it.

“I’m pleased with the process as a campus-wide decision,” Greiner said. “I’ve worked in institutions that have used both policies, and there are pros and cons to each. As a faculty member, I always gave midterm grades. We all teach differently with different approaches, methods, and timelines, so I understand if there is nothing to measure before midterms.”

“Most students like to know their progress,” Greiner said. It’s an individual thing that a student deals with, and it is a hard thing to generalize as every student is different. If they have a ‘C’ at midterm, he or she might see that as call to say, ‘I’ll work harder.’”

Dr. Keely Camden, Dean of the College of Education, has no problem with the current midterm grades procedure.

“It doesn’t bother me one way or the other,” Camden said. “I would want to know my grade, so I should provide it to my students. I know the students who care about As, and it is a concern for them to be able to know their grade. For them, if you have an A at midterm, you’d have to keep it up. I encourage students to track their progress.”

According to Camden, the larger issue lies in determining what a student’s grade actually reflects.

“There’s a general disagreement as to what a final grade really means,” Camden said. “Some would think that an A reflects standard understanding of material, but some instructors view a C as an average grade; it’s contradictory.”

“I think grading can be esoteric,” Camden said, meaning that it may not be easily understood by students. “If I’m looking at a grade, it should be based on content and performance. I’d rather use a system of outcomes and base the grade on how well you’ve mastered it.”

“On scales that factor in disposition and attendance, I don’t think it’s reflective of what one learned,” Camden said. “Attendance can be used as a ‘carrot stick’ for grades. So, I create an environment for students to want to be there, but also makes it difficult to do well if you won’t be there. The more transparent we can be, the better, so there is no question as to where a student stands.”

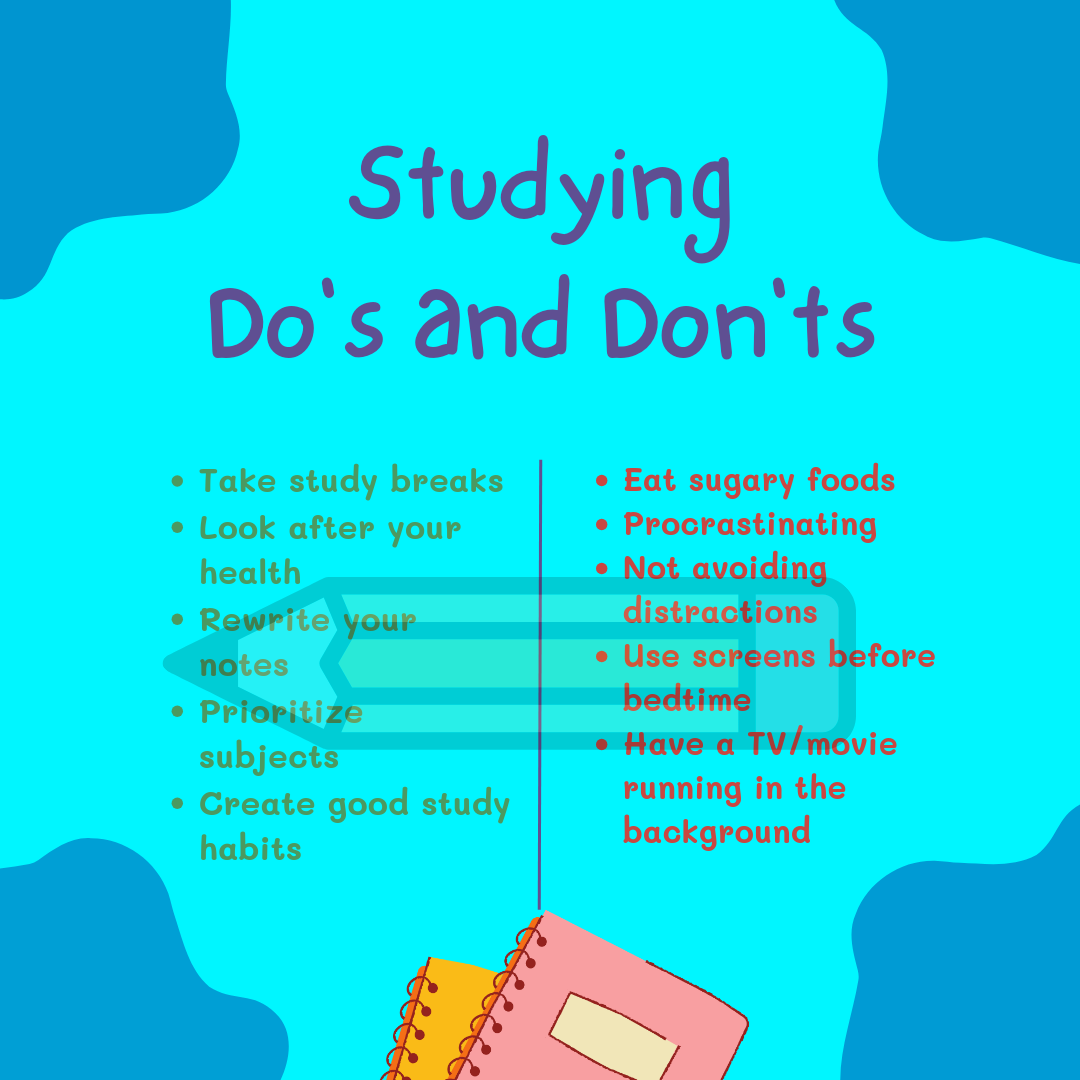

It is highly unlikely that the midterm policy will change, and in reality, it should not change. From a student’s perspective, I believe that we deserve to know where we stand, and midterm grades are a definite opportunity to measure our academic performance halfway through a semester. However, students should not, by any means, rely on midterm grades as sole indicators of course progress.

“I strongly encourage students to stop by during office hours if they want to discuss how they’re doing, and I’m sure most if not all professors feel the same,” Beagle said. “That way, the students will get a fuller sense of not only where they stand, at midterm or any time, but also how to improve their grades before it’s too late.”

“I value one-on-one conversations with students,” Greiner said, “and talking about grades is more direct in helping students know how to pick up their game. One-on-one conversations give faculty the chance to be a mentor, be a coach, and be encouraging.”

Midterm grades are important in keeping up with development, especially if students have teachers who do not update gradebooks on Sakai. At the same time, students should not solely rely on a midterm notification for their academic progress. Students should have a sense of where they stand in every course, and this can be done by having conversations with their professors and maintaining their own records.

As for grading in general, students deserve clear guidelines that state what needs to be achieved in order to master material and receive reflective grades. We should not have to play a guessing game to see if we spoke up enough in class or participated well enough to get the grade that we want. Students will agree that there are professors on this campus who need to work on this.